Having read - a lot - a definite way for me to want to throw a book at the wall is when the narrative either loses sight of the conflict or an author struggles to develop one. As a reader, a lack of or an unclear conflict can feel like sitting in a staff meeting without a purpose. Whether you’re a writer who wants to write a more cohesive story, or a reader who’s developing their critique technique, one thing to look for in respect to believable and developed conflict is the main character’s motivation.

Characters - if developed as a round, dynamic, fleshed out character - are motivated to act. Their movements don’t just spontaneously combust into forward movement for the sake of moving plot. If they do, there is a problem with author insertion and adding to a reader’s awareness of a plot feeling contrived. If you aren’t sure why a character makes a choice in the action or dialogue, or feel confused by it, chances are the character’s motivation isn’t clearly defined or the author is intruding.

With respect to characterization and conflict: do you ask your protagonist, antagonist these questions?

Motivation for a character, just like in our own lives outside of the pages, can be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation is the internal means of propelling a character based on internal desires. Harry Potter, for example, in The Sorcerer and the Stone (J.K. Rowling) was motivated to understand who he was outside the Dursleys. He wanted to know more about his past which propelled him on a journey toward personal enlightenment. Intrinsic motivation. Frodo Baggins, in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (JRR Tolkien), however, was motivated to get the one ring out of the Shire in order to keep his home safe from an external danger. Extrinsic motivation. While the stories begin with a specific sort of motivation - internal or external - this doesn’t mean the motivation won’t change. We see both Harry and Frodo undergo changes along the journey to change what motivates their choices, just as that occurs in our own lives.

I took a wonderful class many years ago that helped me as a creative writer. The class was called The 90-Day Novel by Alan Watt. Character motivation was one idea which really stuck with me. A simple tool Mr. Watt presented which I have used over and over in my own writing is the following sentence:

If (Main Character) can (fill in the blank) then s/he can (fill in the blank).

Here’s an example from Star Wars: A New Hope:

If Luke Skywalker can get off Tatooine then he can be happy.

This is Luke’s reality in the opening of the movie. A clear motivation which propels his curiosity. The longer we follow his journey, however, his initial motivation shifts as the he moves forward in the hero’s journey. When his family is murdered, his motivation shifts. This is a mirror to reality; our motivation is constantly shifting based on attained goals, redefined wants, and personal desires.

So to mirror Luke’s shift in motivation:

If Luke Skywalker can help the rebellion he can avenge his family’s death.

It is important to follow the motivation to the root, however. As the above example shows there are still questions: Why does Luke want to avenge his family?

If Luke can avenge his family then he can clear his conscious for leaving them.

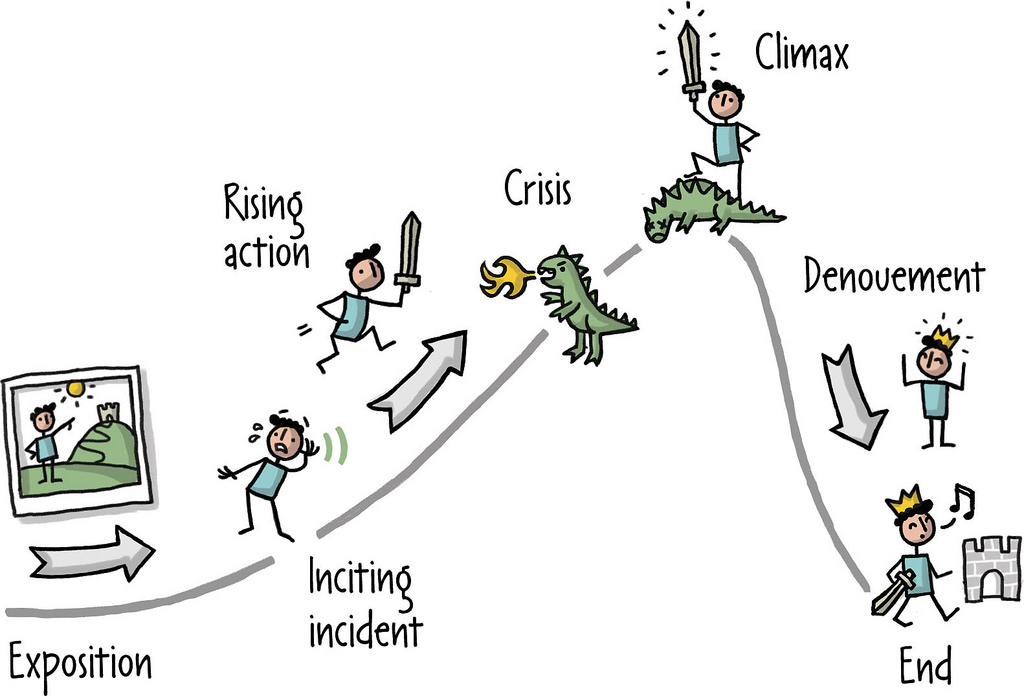

A round and dynamic character’s motivation will always modify and shift as the journey shapes her; that is what makes her more relatable to readers. These changes in motivation whether intrinsic or extrinsic are often rooted in the journey (which if you aren’t familiar with Chris Vogler’s work on the Joseph Campbell monomyth be sure to look it up). As the story moves forward, the motivation serves as a guide for interaction with other characters, propels the main character’s choices, and determines forward action which is believable rather than contrived.