Join me in reading my books with me!

On Instagram, I’ll be reading along with readers this year. Here’s the year at a glance:

Join me on Instagram! We’ll start with Swimming Sideways in January.

Join me in reading my books with me!

On Instagram, I’ll be reading along with readers this year. Here’s the year at a glance:

Join me on Instagram! We’ll start with Swimming Sideways in January.

When I was 18 (this was in the early 1990’s), I was a small town girl living in a very conservative community where God, Family, and Country were the trifecta of life. Everyone had guns and used them for hunting season. It was commonplace to get married young—barely out of high school—to your high school sweetheart. All those beliefs perpetuated year after year. I say this to give you a frame of reference about my perspective at 18. I wanted to go to college, but I was the first one in my family to think about it. We didn’t have a lot of money or know-how about how to get there, but I did think: maybe there’s something else.

One thing I loved: reading.

We had one bookstore and a library. That’s where you could find me if I could find my way to either place.

As an adolescent, my favorite reads were romances. I started with the Sunfire Romances (long live the love triangle) and moved on to Sweet Valley High and Sweet Dreams books (oh the drama), and eventually I found my way to the adult romances reading Lavyrle Spencer and Judith McNaught (so that’s how sex works). I suspect that these readings shaped my belief system about my identity as it related to “romance” and relationships, though to be fair, I had an excellent model of a respectful relationship between my parents.

Like any adolescent, I was ready to test the waters of relationships, and that’s where things got skewed. My fundamentalist, church background—reinforced by my parents—insisted that I shouldn’t date until I was sixteen. When I did venture into the dating arena, I was given a “purity ring” to reinforce chastity (no sex until there was a “ring on it”, peeps) which also loaded on a heap of guilt when it came to experimentation. Finally, I had this “romanticized” version of what it meant to be in a relationship, and no clarity on what an unhealthy one looked like.

Fast forward to 2022.

I didn’t marry my high school sweetheart. I moved away from that small town. I did get to college by the skin of my teeth and graduated. I did marry my college sweetheart and have been a mother to two amazing kids. I got my masters, have worked with teens, and I still read.

Last year, I read the tiktok, booktok sensation Ugly Love by Colleen Hoover. It’s an entertaining book, and while I’m about to be critical of it; please know that this commentary isn’t a knock on the author or her ability to write a catchy book that draws a reader in. This is not that kind of criticism.

When I finished and set Ugly Love down, I walked away from it with my stomach in knots. At first I couldn’t figure out why. It’s about a young woman in her early twenties who’s starting over in a new place. She’s just gotten a job as a nurse and moves in with her brother as a stop-gap until she can find her own place. Living across the hall is her brother’s best friend. There’s a lot of sexual chemistry between them, and so they both consent to a relationship with “no strings.” Except, like most “sex-only” relationships, feelings happen. What ensues is a story highlighting an often unhealthy and manipulative relationship rooted in emotional bankruptcy and trauma. Like any romance read, it ends with the “happily-ever-after” but after reflecting on what had bothered me about it, I realized I had read a glorified version of “If I stick around, I can fix him”, and I felt so sad for 18-year-old me. Why? That girl would have taken the message to heart. I wouldn’t have been able to separate the “romanticized” ideals with reality, even knowing it was fiction.

Which then made me wonder: how many young women 18+ are reading books like Ugly Love (and believe me when I say there’s a lot of stories like this perpetuating a kind of “I can fix him” message) and taking to heart that message? Being set up to accept abusive behavior in a partner because it’s important to be “committed” or if she just “works harder”, then everything will turn out okay.

When I wrote The Stories Stars Tell, there was catharsis for me—the girl steeped in purity culture—to let go of those unhealthy messages about personal empowerment. I didn’t start the story knowing that was where it ended up. I didn’t start The Messy Truth About Love thinking that I would look at that unhealthy packaging of a relationship as “normal” and deconstruct it by reinforcing a healthy relationship. But that’s where it went.

And so that’s what I hope readers are able to take away from The Messy Truth About Love. Sometimes we don’t know we're in an unhealthy situation until we’re able to step out of it and look back as we walk away. And maybe, just maybe, The Messy Truth About Love will be the story someone needs to see their own situation or prevent one. I can hope.

Before I met my husband or moved to the Kingdom of Hawai’i, my knowledge about it was rooted in the gifts my grandparents would bring back from their visits: the touristy plastic lei and the “hula” girl doll that rocked back and forth decorated in the grass skirt and coconut bra. I knew it was really far away and that my grandparents had to take an airplane to visit. My young brain understood it by the exotic perpetuation of stereotypes reflected in the media. I remember Magnum PI (the Tom Selleck version), the Brady Bunch visiting Hawaii, and Saved By the Bell: Hawaiian Style, for instance. These stereotypes shaped my understanding about Hawaiʻi.

The first time I ever visited, technically, I didn’t journey here as a tourist. Instead, I visited Hawaiʻi as a guest of my boyfriend to stay with his family. Though he took me to see some “touristy” things, I got to experience Hawai’i immersed in the reality of living and working in this place. After getting married to that boyfriend, I moved here, but it didn’t connect that I was moving to a place illegally occupied by the United States. Truthfully, in 1997, I didn’t think much about it at all. I had just married my Hawaiian husband, who I just assumed lived in the fiftieth “state”. It had only been 100 years earlier that Hawaiʻi’s Queen Lilioukalani was held prisoner in her own home and forced to sign a “treaty” which eventually led to Hawaiʻi’s annexation as a US Territory in 1898 and was ratified as a “state” in 1959.

But this isn’t what we’re taught about Hawaiʻi on the mainland.

The oversimplified gist of those events is that a group of white, American businessmen descended from the white, American missionaries, who settled in the kingdom—in order to protect their business interests—leaned heavily on the queen to sign control of the kingdom over to the American government. When she refused to kowtow to their demands, she was seized and held prisoner in her own home until she signed the “treaty”. There are a ton of books written out there about it by people much more knowledgeable than me [and if you're interested, I would highly recommend starting with Queen Lilioukalani’s journal Hawaiʻi’s Story (1990)].

Unfortunately, there are more people like that 1997 version of me. Many people in the contiguous United States are unaware of the political history of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi—it’s geographic isolation is just one reason it might not show up in a US history lesson, but let’s be real, that isn’t the only reason. I didn’t learn about it in school. Considering my own education in a rural area of Oregon, I barely learned about the native First Nation people indigenous to my own area (which I now know to be the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin Tribes). My education about nonwhites (and keep in mind this was the late 1970s and 1980s—I graduated from high school in 1992) was filled with what I know now to be unbalanced content that perpetuated all the stereotypes, reinforced white bias, and the heroic propaganda of the Mein Kampf . .. oops, I mean, US History textbooks: Colonialism? What is that? Like settling the first 13 colonies to get away from religious persecution? Here’s the definition: Colonialism is when a country sends settlers to a place and establishes political and cultural control over it. So those missionaries that turned into land holders that turned into business men pushing their own religious and political agenda onto the indigenous population. Yeah. Colonialism.

I had this epiphany the other day that colonizers are like invading aliens. Now, please don’t align my use of the word “alien” with the way the United States right-wing has used the term to identify undocumented people trying to seek asylum and better conditions in the US. Not the same thing. My use of the word alien should conjure more of the War of the World sucking up human bodies as fuel connotation. And we love those movies right? Mars Attacks!, The Edge of Tomorrow, Independence Day, A Quiet Place to name a few. Each of these stories offer the premise that the human world is being infiltrated by an extraterrestrial, alien species bent on colonizing the planet (stealing resources, but same difference) and the people rise up and heroically fight against the monsters.

You see the irony right?

But know that this isn’t an essay on white guilt, but instead an acknowledgement of the reality of the state of things in Hawaiʻi. Nor is it an essay meant to perpetuate a xenophobic ideology. I wanted to offer a perspective of someone outside that indigenous perspective who IS the alien invader—albeit a welcome one, because there is power in sharing the truth of things. I am not Hawaiian. I’m a guest on this land (ʻāina), and it’s very important that I understand it, just as I hope I would of any place I visit.

Just as I hope that you, too, would understand Hawaiʻi on a deeper level when you visit.

I’m sorry to say there is no one more entitled than a tourist. On one hand, they’ve spent a lot of money on a “dream vacation” so they want their idealized dream, but on the other, they are occupying someone’s home where that dream isn’t real. A common thing I always hear from tourists is: People should be happy we visit. Tourism creates jobs and puts money in the economy. Okay. Get that, but let’s take a closer look. If you were to just take in the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority data, you’d think tourism makes Hawaiʻi a boomtown. But just like my oversimplified gist earlier, that’s an oversimplified argument filled with unaccounted for nuance and context.

Here are some numbers for you:

The median income in Hawai’i is around $37,000.

The cost of living in Hawaii—in order to make ends meet—is listed at *$70,000 *though other sites have cited “to be happy in Hawai’i,” a household would need to bring in $195,000 (this is more reflective of an income with the ability to contribute to savings and retirement).

The median rent is $2,300

The median home price is $810,000 (which with a 20% down means financing $648,000) Do the math. Even making the $70,000 dollars isn’t going to get you a home.

Hawaiʻi’s minimum wage: a whopping $12.00/hour.

The average tourism job starts at $12 - $17/ hour. And you know . . . come on, you know… most corporations aren’t hiring workers full-time in order to avoid paying benefits, so people are working double, triple jobs to afford living and health care.

Those abysmal numbers highlight the average means for a resident of Hawaiʻi. While the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority cites collecting upwards of $2.6 billion dollars in tax revenue, this money doesn’t impact the day-to-day lives of the average person in Hawaiʻi struggling to make ends meet. Then their resources (water, sewage, air quality, sea quality, food costs, housing costs) are tapped by the massive influx of invaders—the tourist—whose tourism dollars would have to be spent in Hawaiʻi owned business—Hawaiian owned shops, in Hawaiian owned restaurants, in Hawaiian owned boutique hotels, to actually benefit the people with their tourism money—but this isn’t the case. Most tourism dollars are spent supporting the conglomerates (chain hotels, chain restaurants, chain stores) who pay their workers minimum wage.

There’s the argument that assumes someone living in Hawaiʻi can find a job outside of tourism. Except it's a machine which means every family in Hawaiʻi is impacted by this industry. Even if the local population wanted to boycott tourism, they couldn’t. Do you think it’s the dream of those hula dancers to dance at the Hotel Luʻau? Case in point: my oldest child has a college degree and the only position that seems to be open after months of looking for full-time employment is a position at a hotel.

So here’s another oversimplified gist: tourists and non-Hawaiians accessing the land and resources are benefiting the bankroll of the businessmen. And those businesses are protecting their business interests—not aligned with Hawaiian ideals—and leaning heavily on the working-class of local and indigenous people who live here, who benefit very little in the day-to-day of their lives. I know Hawaiians have a lot more to say on this topic and I won’t presume to speak for them, but I know many who have gone so far as to say, “don’t come here without an invitation from someone who lives here.” If you think about it, that’s actually a great practice—that was my first visit to Hawaiʻi, remember? How much more do you appreciate and take care of a place when you visit knowing you’re guests of friends?

A few years ago—pre-2020—my husband and I had the opportunity to travel to Europe on a river cruise down the Danube. One stop in particular sticks out in my mind. It was in a small river village in Austria, and it was clear that the village was reliant on tourist dollars, but also that there was more to the town than what we could see in the six or seven hours of our stop. Most of the tour group—fifty or sixty of us—decided to go to a local winery. We sat in the tasting room and listened to the vintner tell us about his products, then we were given samples of the wine. It was a picturesque location vibrant with local flare. What stood out to me, however, was the way several members of our American group were behaving. They were loud, interrupted the man speaking, laughed loudly (and since there was a language barrier, one might assume they were being laughed at). I was mortified by their behavior, so ashamed.

Having been in Hawaiʻi now for nearly thirty years, I have witnessed this kind of behavior by alien invaders. The trash left on beaches, the entitled attitude about space because “do you know how much I paid for this vacation?”, the lack of regard for the real people taking care of them in service jobs. One time my husband and I took my visiting mother for breakfast on the beach. When we arrived at the restaurant, my husband approached the host podium to get on the list for seating when a tourist looked him up and down, then sneered as she said, “I was here, first,” to which my mother replied, “I think he’s been here longer.” The tourist didn’t get it.

And that is where the problem lies. Invaders and occupiers take. And even in spite of that, Hawaiian culture is all about hospitality and generosity. Nana Veary, Hawaiian spiritualist wrote in Change We Must, My Spiritual Journey (1989) about a lesson she learned as a young girl when her grandmother invited a stranger to come in and dine. She didn’t understand why her grandmother would feed him to which her grandmother replied in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, “I want you to remember these words for as long as you live, and never forget them. I was not feeding the man; I was entertaining the spirit of God within him.”

That gracious hospitality still exists in Hawaiʻi and is inspiring. I would argue that for that generosity to continue, there needs to be a reciprocal nature to the host-tourist relationship. Do you show up at your friend’s house empty handed? Your parent’s house? What about the brand new neighbors to the neighborhood? So here’s some food for thought: As an alien invader… ah hem…I mean as a tourist to Hawaiʻi (or any other place for that matter) what are you giving to the space that you occupy? Are you bringing anything other than your entitlement and your trash? Take some time and learn about the real place, the home, the land you’ll be occupying rather than fetishizing it and snagging the cheap, plastic hula doll you’ll stick to your car dash so you remember lying on Waikiki Beach that one week that one summer.

There are quite a few stories about people coming to Hawaiʻi to visit, then never leaving. Hawaiʻi is an amazing place, so I can understand the attraction (though I do have mixed feelings about it). My story, however, is a little different…

When I was eighteen, I went off to college. Ah hem. Okay fine. I didn’t even leave my hometown. I enrolled at my local college, started going to classes, and was well on my way to flunking out—yeah. I had no idea why I was there— when I met a guy. In hindsight, that exact reason was probably why I was initially there (which is a completely different story). His name was Vince, he played football for our college, and he was *Hawaiian from **Hawaiʻi.

*Quick lesson No. 1: I’m from Oregon. And as with most states in the United States, we tack on an -ian at the end of the world to indicate our state of origin. I was born and raised an Oregonian, for example. The same isn’t true for Hawaiʻi. People who live in Hawaiʻi aren’t indicatively Hawaiian, even those who were born and raised here. Hawaiians are a native group of people who are indigenous to Hawaiʻi. It’s disrespectful, then, to say that just because I’m from Hawaiʻi that I’m Hawaiian. I am not. The proper term would be to say I am “local”. For an interesting take on the origin of being a “local” in Hawaiʻi pick up John Rosa’s book: Local Story: the Massie-Kahahawai Case and the Culture of History.

*Quick lesson No. 2: I used to pronounce Hawaii as (Hah-why-ee). That, my friends, is incorrect. The correct way to pronounce this amazing place is Hawaiʻi (Huh-vī-ee—making sure that second sound—vī—is short and sturdy).

Long story short, after Vince and I dated, eventually making things exclusive, the school we were attending dropped the football program. Vince decided to transfer to play football for another school and suggested I transfer with him. I may not have known why I was in school yet, but I did like the guy. Why not? So off we went.

I did finally figure out why I was in school—majored in English—and we continued dating while we went to school. Our relationship turned into the five-year variety, and we got married in 1997. And then I moved to Hawaiʻi (did you say it right?) that same year. Married for nearly 26 years now, I’ve lived in Hawaiʻi longer than I lived in Oregon. I am so grateful to call Hawaiʻi home.

(You can find this post on Substack, here.)

You know that party question: would you go back to high school? It often creates an either-or dichotomy: Hell no! Or Absofuckinlutely! For the last eight weeks, I went back to high school. Okay, not as a student, but rather as a long-term substitute teaching English to 9th grade students. Given I taught English for over twenty years, this wasn’t a stretch, but after nearly three years outside of a traditional classroom working instead as a full-time author, it was a refresher in all things teen and work life. This, my friends, is what I learned returning to the classroom.

First, kids are kids no matter the year. Granted, the 13-and-14-year-old students I was attempting to impart wisdom about Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet were eleven when they were forced home for Covid. So their sixth-and-seventh-grade years (a primary time in learning communication skills) were spent behind computer screens (and believe me it showed). I got them journals to decorate and make their own and each class we spent writing for the first ten minutes. Then—to practice our social skills—we “turned and talked” and like any teen, they fell right into that activity. It took a bit of time to get them to share with one another, but after a week or so, it began to feel safe, normal even. Teens are awesome people. They’re funny, they’re pragmatic, they’re focused (on what they’re interested in), and like all people, they're social.

Sometimes I get so far into my head, I forget the socialization part of life. I’m a self-professed introvert. I am content in my home, in the space I’ve made for myself, in the routine that I’ve created to address my work (writing, editing, book life, and taking care of the dogs and cats). I’m content to text with my friends and set the phone down. This isn’t a knock on my friends or human interaction in general, just a truth about my identity. I am content being alone. But walking into the classroom and observing the students reminded me how important socialization is. How critical it is to interact with others in order to grow my perspective, challenge my norms, push me outside of the comfort zone. I’m better for it. Just like the students, I have to make time to “turn and talk”.

“Make the time to ‘turn and talk’.”

Second, I remembered immediately how much mental capacity is necessary to be a teacher. Goodness gracious. There’s creative work of designing the curriculum and making sure it’s got enough critical-thinking meat as well as age-appropriate relevance. Then there’s the creativity in doing the same for each class-period lesson. Then there’s the all-encompassing act of assessment, whether it's the informal observation in the classroom, the formative assignments, or the summative tasks to showcase skill growth, a teacher is always “on” both inside and outside of the classroom, and it’s exhausting. From the classroom management, to the planning and assessment for each learner, to the research—and while I didn’t have to attend all those meetings—there are all those meetings that really have nothing to do with the day-to-day job, but the bigger picture of teaching and learning.

I had a conversation with one of my former colleagues (yes, this is the school where I used to work full time before leaving to write full time) who expressed the day-to-day struggle. Having been teaching for fifteen years, *they indicated a sense of bone-weary exhaustion. Is it a wonder? The amount of mental capacity it takes to do the job coupled with the struggle of external perception that “teachers don’t do enough” along with administrations who add to the plate for “accountability” is not only disheartening, but drains the well dry.

When I sit down at my writing desk everyday, I feel joy. The act of creating, of telling a story or sharing my thoughts, is fulfilling. I might be poor, but I am so content doing this work. And while that creativity does draw from the well, this is a choice I make each day. I’m accountable to myself, to my own perception of what’s going to build and present my best work. This conversation with my colleague reminded me how unfulfilled I felt as a teacher. Don’t get me wrong, there were absolute moments of fulfillment. That moment when all the work that went into that unit and specific lesson hit all the right notes, when I got that student essay that nailed it, when I had a real conversation with a student that helped them through something, or the plethora of moments with colleagues when we laughed and planned and continued through the struggle together. But overall, my mind was always thinking about writing. Makes sense—it was what I was born to do. And that—time spent pursuing my passion—is so affirming.

“You canʻt ever go home again”

Finally, Thomas Wolfe in his 1940 novel by the same title wrote, “You can’t ever go home again.” I disagree with the sentiment. We need to go home again. It’s true that when we return home, we return with a new perspective, therefore we aren’t able to capture that experience with the sameness of our memories. It’s impossible because we are changed. New perspective allows you to see with new eyes, while at the same time grounding you to something familiar. Returning to my former school allowed me this renewal. I returned with three years of independent authorship and entrepreneurship added to my vitae, and while that impacted my experience of walking back into the classroom, being a teacher again offered me the familiar feeling of being good at something once more when authorship doesn’t provide that immediate feedback.

As I was standing in the hallway greeting students as they passed, welcoming my students to the classroom, one of the vice principals walked past. It was my last official day in the classroom, and we exchanged chatter about it. *They continued on, but then stopped and backtracked toward me once more. “I wanted to tell you,” they started and expounded about a teacher group I was a part of with them before I left. We reminisced about the power of that group, and the change we were able to enact because of our work. Then they said, “All that to say, you made a big difference in our school. Thank you.”

I don’t take compliments well. Never have (Iʻm sure there’s a bunch of psychology behind this), and I felt speechless. It was such a nice thing to say, and this person didn’t have to backtrack to offer it to me. I walked into the classroom, pondering it. I think perhaps I even attempted to discount it, but it couldn’t be dismissed. I had to take that sweet sentiment and allow it to bolster me. And it did. It reminded me that risk-taking for the greater good is a very important part of my identity. So perhaps you can’t go home again unchanged, but home often has a way of reaffirming ourselves and strengthening our purpose.

So, friends, I return to my writing desk full time, surrounded by my furry co-workers—Ruby, Haupia, Cheese, and Happy—ready to face the quiet of my writing life, excited to face it, and grateful for having taken the time away to refill the well in a different capacity.

I will be moving over to SubStack for additional content. While you’ll still have access to this weekly blog, perhaps consider subscribing to my substack for up-to-date news and additional writing excerpts meant to entertain.

*They denotes a singular person and is used to protect their identity.

When I was in my early twenties—an English major—I wanted to be a writer. I knew I wanted to be a writer before that even, when I would choose to sit at home and pen stories over going out with high school friends. Or when I would close my latest Judith McNaught reread and think: I want to do that. Even before then, when I wrote my first story at eight and read it out loud to my mom.

I read recently in a book by Deepak Chopra called The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your Dreams (1994), the seventh law was the Law of Dharma or Your Life’s Purpose. To paraphrase Chopra (definitely check out the book if you’re interested), each of us is born with unique talents and a way of expressing it that is original to us. In conjunction with that talent is a set of personal needs matched up to that talent which can only be expressed by us. By fulfilling this need utilizing our talents, we will find fulfillment.

I understand this. My love and desire for writing and stories started early, and my proclivities and knack for it always leaned in that direction. That doesn’t mean, however, that at eight, or sixteen, or twenty-six, I was prepared to achieve the dream. There was work to do.

Case in point: One of the first novels I wrote (not the first. That one sits in a proverbial eDrawer collecting electronic dust), was The Letters She Left Behind, a romantic suspense that follows Adam and Alex on an adventure to catch a killer, all while given a second chance at love. I was around twenty-seven when I wrote it, a new wife of three years, a new mother. My main characters in this story, however, are in their late forties and dealing with things like grief, being widowed, and the empty nest. Needless to say, at twenty-seven, I was ill-equipped to write this story, severely lacking experience to give it justice.

“Talent is nothing without hard work”

While I think we may have a talent or a knack for something, that doesn’t mean it is’t necessary to build the skills necessary to do it. When I look at The Letters She Left Behind (which was rewritten in 2019 and published in January 2020) I can see how much I have grown as a writer since, how much experience I’ve gained. How much practice I’ve devoted to the craft. I love how footballer Cristiano Rinaldo tweeted once, “Talent is nothing without hard work.” I have had to work hard to develop those natural talents toward writing.

When I reread The Letters She Left Behind, sometimes I think I should rewrite it and re-release. Then I think that would be a disservice to who I was as a writer and all the ways I grown since. It’s good to look back over the bridge to see where I once was to appreciate where I am at now. And hopefully, I’m always working hard to grow.

So in honor of the anniversary of the publication of The Letters She Left Behind 3 years ago, here’s to working hard and growing.

Also, here’s some previous blogs I wrote about this book:

Dear Friends,

I was sitting at the beach the other day, drinking my coffee, watching the ebb and flow of the waves as the tide came in. The sun was warm against my face, and I thought about how though life feels static, it really isn’t. I sat on that beach for nearly an hour, and recognized the tide coming in because waves came in, drew back out, came back in, cresting and washing over the shore until a rock was submerged under the water. It was exposed and dry when I arrived. The tide is subtle and if I hadn’t been paying attention, I might never have noticed it.

One of my dreams as an author is to be able to make a living creating. Am I there yet? Nope. Not even close. (Thank God for my husband, who’s supportive of this dream, my mom, who supplements me when she can, and for each of you, willing to buy the books when they drop. You all probably have multiple copies of each). While I might feel discouraged sometimes at how little impact my ripples are making in this giant ocean of writing and publishing books, as I sat on the shore watching the tide, I realized that what I’m doing isn’t static. There is a dynamic ebb and flow to it, moving me forward toward my goal.

It’s subtle.

So this February I’m going to remember that. The steps I take, the moves I make, the people I talk to, the list of things I have to do are all contributing to that rising tide. My job is just to keep doing what I do with a joyful heart filled with gratitude.

Thank you for being on this journey with me,

Cami

Click the button below for a link to a sample of my newsletter. Subscribe today!

If I thought selecting the favorite books from the stack I’ve written was difficult, choosing my favorite characters is infinitely worse. Why? I love (or love to hate) them all, but for the sake of this exercise and not because I don’t love these characters (who are like real people in my head), I will go through with this top 5 list. Here’s the criteria I used to help me decide:

Characters I’ve already written, not ones I’m in the process of writing.

The challenge of writing the character and the overall outcome on the page.

The way the character lingers in my mind after finishing the story.

How the character presented on the page with other characters

This presentation is in no particular order.

Truthfully, Tanner James from The Stories Stars Tell, jumped from the pages the moment I started writing his character. He was funny, daring, and heartfelt, but stuck in his small world. I loved getting to know this character and all the ways that his life influenced his choices. The first scene I wrote with him was the cliffside scene (I posted it to Instagram in a Sunday Snippet, here). The more I wrote Tanner, the more invested I was in The Stories Stars Tell.

Tanner’s antithesis in The Stories Stars Tell also tops the list. Here’s the truth, I struggle to write female characters. I’ve written about this before (want to read that: here), so when I stack up writing Abby, which was really the only other female character I’d written for ten years with Emma, I was able to present a more fleshed out young woman in Emma than I ever had before.

I have decided to present this couple as a single character. Okay, this might be cheating, but hear me out. Griffin was really hard to write, and difficult to like initially. When you read The Stories Stars Tell (he’s Tanner’s best friend and not very likable) and In the Echo of this Ghost Town, he is so flawed right at the onset. Enter Maxwell Wallace (specifically the gas station-convenience store scene which is the first moment I met Maxwell) and suddenly Griffin popped off the page. As character’s go, Maxwell is the shiny light and Griffin is a grump. She really makes him, but she also makes the story. I could have just picked her, but I feel like it’s their relationship on the page that makes them both so dynamic. So I’m sticking to this choice.

True story: Gabe started out as a fallen angel, and in the original story Upside Down (it’s here on Wattpad if you want to read it but please forgive me. It’s not great. I was just getting started finding my own voice). He was this idealistic, mysterious outsider who was over-the-top heroic. Obviously, I couldn’t get this Twilight wannabe story to work, but I couldn’t figure out why. Not yet, anyway. While revising, I wrote this horrific scene which I can’t divulge here (it’s a spoiler) and I had this minuscule voice in the back of my heart saying, “that’s me.” I knew it was Gabe talking to me, but I was terrified to write that story. It didn’t go with the original paranormal idea, and it was dark. Really dark. In hindsight, my journey hadn’t taken me anywhere where I could have written that story and given it justice yet. I needed time. So, fast forward seven years after I rewrote Swimming Sideways and The Ugly Truth as contemporaries and that scene resurfaced. Gabe said, “See. I told you it was me.”

I feel like Seth started my whole journey, so he has a very special place in my heart. While I’ve been writing since I was a child, and I've written at least four other books (unpublished) before publishing Swimming Sideways, Seth’s character is the one that wouldn’t stop talking to me. Seriously, he’s a freaking nag. To be fair, if you’ve read Fallen (that Wattpad Monstrosity again), I left him trapped in the underworld, so his nagging was about getting him out (LOL), but then I changed everything up on him, and discovered he was trapped in the underworld in this world, not a fantasy one. Which led to The Ugly Truth.

I couldn’t leave it there, because I think secondary characters are amazing, and I have some really loud ones talking my ear off at the moment. I figure I’d share some that I was really proud of and loved writing:

Cal Wallace (In the Echo of this Ghost Town & When the Echo Answers)

The entire cast of secondary characters from The Stories Stars Tell. I mean really? Who doesn’t want to read more about Ginny, Liam, Josh, and Danny? What about Emma’s sister, Shelby?

Dale and Martha from The Bones of Who We Are. I especially loved writing Dale.

There’s a bunch of new characters showing up in some new stories I’m working on, but those are top secret for now. Join my newsletter if you’re interested in hearing about those books before anyone else.

It’s the final update for the April Challenge. There’s good news and bad news.

I’ll start with the bad: I didn’t write everyday.

I have learned this month that an important part of my writing process is the necessity to step away and allow the story to rest while the flavors meld. It reminds me a bit of that space between a finished draft and a revision. When I attempt to force it, I mess things up—like globbing on too much makeup— and then have to do a lot of rewriting. When I’m patient, however, I’m able to approach the writing with clear understanding and perspective. So this month, those goose egg days were time spent away, but time thinking things through.

So, the good news is that this first draft is complete even if it’s only bones. Better yet, I have a sense of how to revise! Hooray! Hooray! Hooray!

I must share some credit for this breakthrough. My wonderful writer friends, Brandann R. Hill-Mann, author of The Hole in the World series, and Stephanie Keesey-Phelan were gracious enough to read the first act for me. Brandann offered me this golden nugget: “What would happen if this story occurred in a white room, removing the setting?” The obvious outcome is that if you can remove the story to a white room and the story essentially remains the same, the setting either doesn’t matter OR the setting isn’t working hard enough to help tell the story.

Lightbulb moment!

I realized while I could remove this story to a new setting and still have a story, that wasn’t my problem. I’ve written strong characters, and one of my strengths as a writer is being able to write character driven narrative, but plot driven narrative, which is important to fantasy as a category, is sorely lacking. My problem was that I hadn’t weaved the setting enough into the conflict to support the plot driven element.

So dear friends, I’m smiling as I finish out this April Challenge, because I have a draft, and I have a sense of which way is forward. THAT is exactly what I’d hoped to achieve. Time to set this book aside for several weeks, work on that setting and conflict, then it’s time to revise.

On Sale today, where ever books are sold. Hooray!

We did it. We made it to the finish line, and The Cantos Chronicles are out in the world today. How we did remains to be seen, but here’s the feedback on our journey:

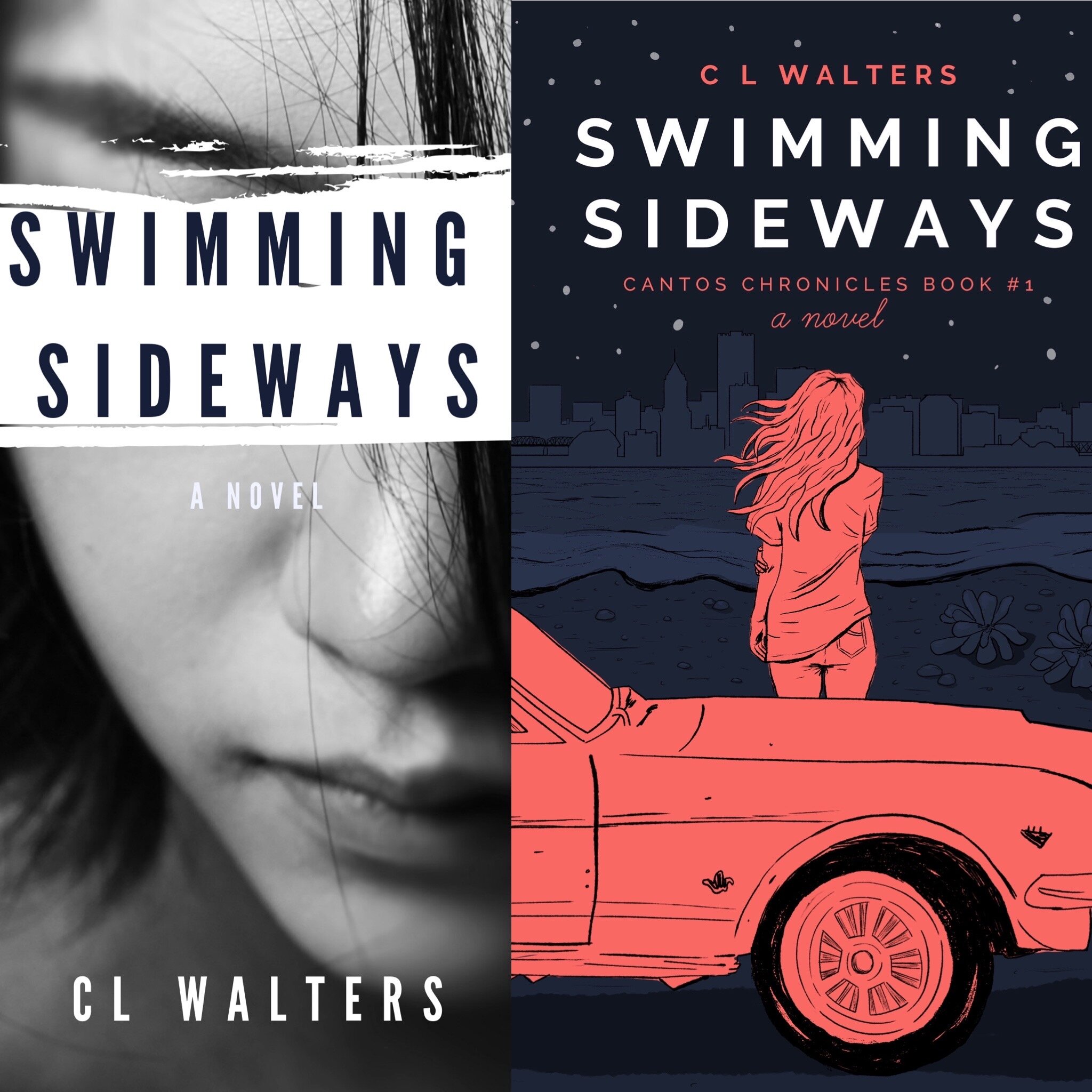

This was the first thing that was mentioned as a ”stand out” in terms of marketing these books. This doesn’t surprise me (and probably doesn’t anyone else either) which reiterates the point that authors (indie authors, specifically) should budget for a cover as part of your marketing strategy. How the product appears matters. That shouldn’t come as a surprise, right? Case in point: Look at the two Swimming Sideways covers (pre-rerelease and post). Which one do you like better?

The black and white was the second cover. It’s a Canva stock image and clearly an inexperienced Indie move. It isn’t the wisest choice when trying to “stand out” in a competitive market. The new cover is designed by a trained graphic artist, Sara Oliver Designs, and is original to Swimming Sideways!

Um. Yeah. The new cover is hands down better than the other (thank you, Sara!)

Shocking - I know - baring who I am isn’t comfortable - naturally introverted, but adaptably extroverted. That means I’m a freaking chameleon. No. Actually, it doesn’t, but I’d like to think it is a super power. Okay. In all seriousness, while being more in the “spotlight” doesn’t feel comfortable, it is a part of building a relationship. There is a give and take between people. What’s your favorite color? Mine is… This must occur, right for that reciprocal relationship building. This doesn’t stop even in a social media world which means we have to put ourselves out there.

What made this difficult for me (besides the whole discomfort of being in the “spotlight”) is the belief that I don’t think I’m all that interesting. I’m just ordinary Cami. Here I am feeling like my brain might be boiling over trying to figure out what’s interesting, and I’m thinking “there’s nothing worth sharing.” Perhaps this is a lie I tell myself because people expressed: I liked getting to know you. Hmm. Who knew? The lesson then: I can’t be afraid to put myself out there; I can’t worry about if what I have to share is interesting or not because I can only be myself; and I can’t be afraid to share my truth.

The methods mentioned were sharing the music playlists, sharing the book lists, and the new content snippets that helped readers feel more connected to the characters. That’s cool (and I wish I could share with you how cool these people are in my head… still!)

One IG follower said that being able to talk about the books with other readers while reading was a little like a “social media book club.” Bookstagrammers have this on lock and are very prolific in this regard. It’s a great tool (though I won’t pretend I’ve figured out how to generate more engagement with this; I think it will continue to be time and consistency).

Well. Here we are fellow road trippers. We’ve parked the van in the garage. We’re popping the champagne. Let’s toast to nine weeks of bumping along this Indie Marketing Road to a job well done. Thank you for being on this journey with me.

What’s next? Not sure. I’m going to take a couple weeks to finish my current book and figure myself out.

Now, I have to figure out how to look at the “after publication” marketing. :)